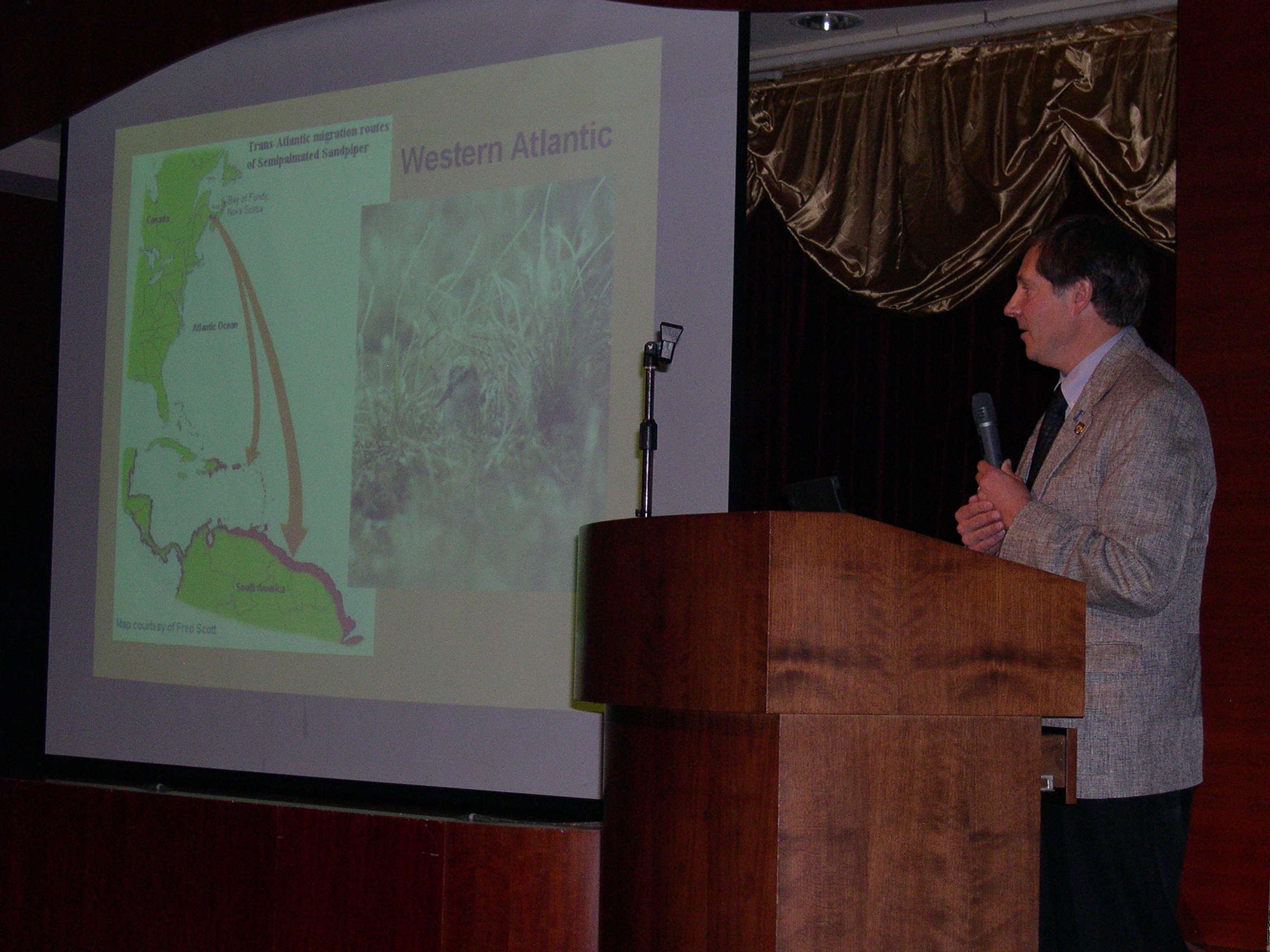

Brad Andres is the National Coordinator of the U.S. Shorebird Conservation Partnership. He works in the Division of Migratory Bird Management at the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, in Denver, Colorado.

Gone in a Gust

The Disappearance of the Wind Birds

About 24% of the world’s shorebird species occur in the U. S. and Canada; they can be found in every state and province. Of 51 shorebird species that breed in temperate, boreal, or arctic North America, most individuals of 40 species (78%) spend their winter in Latin American and Caribbean countries. Other Nearctic-breeding shorebirds travel to wintering grounds in eastern Asia, Australia, Polynesia, and northern Europe. To maintain the eastern Hudsonian Godwit population, for example, we need to provide 1) adequate tundra breeding habitat around Hudson Bay; 2) suitable fall-feeding areas along the U.S. Atlantic coast; 3) prey-dense, contaminant-free tidal flats for winter feeding and roosting in southern Argentina and Chile; and 4) well-managed, productive spring stopover sites in Kansas.

“The restlessness of shorebirds, their kinship with the distance and swift seasons, the wistful signal of their voices down the long coastlines of the world make them, for me, the most affecting of wild creatures.“

— Peter Matthiessen, The Wind Birds

Many species of shorebirds have recognizable populations that nest in discrete areas and migrate to distinct wintering grounds. In general, shorebird populations are relatively small and hence are vulnerable to environmental perturbations. Of 74 distinct shorebird populations identified in North America, about 30% number less than 25,000 individuals, and only nine number >1 million individuals. Eight populations of shorebirds are listed, or have been considered for listing, as threatened or endangered in the U. S.; one species is likely extinct. Twenty-two species of shorebirds were included in National Audubon/American Bird Conservancy’s 2007 Watchlist, and 22 populations have been suggested for inclusion in the Birds of Conservation Concern 2008.

For many species, precise knowledge of their population status and trend is lacking, and no consistent, range-wide tracking system for shorebirds has been implemented. Where information does exist, indications are that few species are increasing, and many populations, including those that are most numerous, are declining. Because migratory shorebirds traverse such a wide geographic range during their annual cycle, it is difficult to determine which environmental factors might be limiting population sustainability. Many shorebirds species aggregate in large numbers during migration, which make them particularly vulnerable to catastrophic environmental events.

Continued loss and degradation of grassland, wetland, tidal flats, beach, and tundra habitats induced by human activity are challenges to shorebird conservation, which stretch across the globe. Tidal flat “reclamation” in the Yellow (Bohai) Sea not only reduces foraging habitat for threatened, Asian- breeding shorebirds like the Spoon-billed Sandpiper and Nordmann’s Greenshank, but may also have deleterious consequences for Alaska-breeding Bar- tailed Godwits and Dunlin. Factors associated with human activity, such as disturbance to roosting and foraging birds and increased predation, have detrimentally affected shorebird populations. Consequences of global climate change will likely accelerate the reduction in quantity and quality of grassland, wetland, beach, and tundra habitats used by shorebirds throughout their annual cycle. In the Arctic, the trophic mismatch of insect emergence and shorebird chick hatch induced by global climate change could have drastic consequences on shorebird reproduction.

The public values healthy populations of shorebirds. People are fascinated by the remarkable accounts of their annual migrations. Their habit of concentrating in spectacular numbers during migration provides excellent opportunities to educate the public about the conservation of birds and their habitats. The growth of shorebird festivals at migration stopovers attest to the public’s interest. The unique and obvious physical traits of shorebirds make them compelling material to teach children, and adults, about the natural world. Long-distance migration of shorebirds links communities, countries, and continents in conservation.

To address the challenges facing shorebird conservation, the following strategies need to be implemented:

1) determine how and where the sustainability of shorebird populations is being limited, both at present and in the future (e.g., climate change scenarios);

2) build hemispheric capacity to development shorebird decision-support tools that result in the most efficient and effective conservation investments (in the U. S., through Joint Ventures);

3) increase protection, enhancement, and restoration of breeding, stopover, and wintering shorebird habitats in areas used throughout their annual cycle (including indirect protection like the development of oil spill response plans);

4) implement shorebird monitoring systems to periodically assess status and evaluate results of conservation or management interventions (efforts like PRISM have been designed and are awaiting implementation); and

5) increase public, culture-specific awareness about the value of conserving shorebirds and their habitat (rejuvenate and expand Shorebird Sister Schools Program).

U.S. Shorebird Conservation Partnership

To address these concerns, partners from state and federal agencies and non- governmental organizations from across the country pooled their resources and expertise to develop a conservation strategy for migratory shorebirds and the habitats upon which they depend. The plan provides a scientific framework to determine species, sites, and habitats that most urgently need conservation action. Main goals of the plan, completed in 2000, are to ensure that adequate quantity and quality of shorebird habitat is maintained at the local level and to maintain or restore shorebird populations at the continental and hemispheric levels. Separate technical reports were developed for a conservation assessment, research needs, a comprehensive monitoring strategy, and education and outreach. These national assessments were used to step down goals and objectives into 11 regional conservation plans. Although some outreach, education, research, monitoring, and habitat conservation programs are being implemented, accomplishment of conservation objectives for all shorebird species will require a coordinated effort among traditional and new partners.

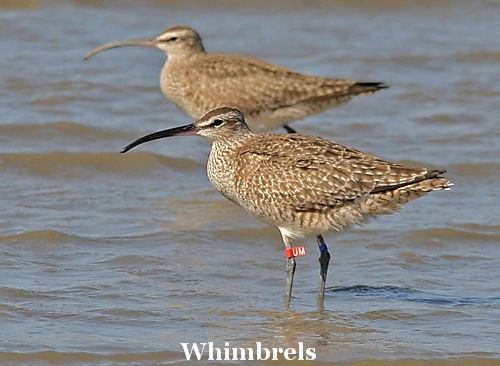

Have You Seen This Band?

Over the last two years, we have been color-flagging Whimbrels and Hudsonian Godwits on Chiloé Island, Chile. Over 20,000 each of godwits and Whimbrels spend the boreal winter in the vicinity of Chiloé. Using a canon-net, we have marked 523 Hudsonian Godwits and 196 Whimbrels. These birds will be sporting a red flag (the color for Chile) that is engraved with a unique two-letter/number combination on their upper left leg (tibiotarsus). Flag letters/numbers are read like we read a book, from left to right. They will also have a combination of a metal band and a color ring on their upper right leg, which is blue, orange, or yellow. Combinations should be read as yellow color band over a metal band. Remember that anatomical directions are the way the bird is facing, not necessarily the way you are looking at the bird. Besides banding the birds, we collected blood, took measurements, assessed molt, and collected samples for Avian Influenza (taken by the Chilean agency, Servicio Agrícola y Ganadero). The blood will be used in a genetics study to determine the origin of the Hudsonian Godwits and Whimbrels wintering on Chiloé Island. Re-sighting of flagged birds will help us determine their migration routes. Please report any flag and color-band observations to Jim Johnson (907-786-3423) or Brad Andres (303-275-2324). We have had re-sightings in Alaska and southern California.

Black Oystercatchers

“Left to themselves, the birds are no Quakers, and the antics of courtship are both noisy and amusing.”

—Dawson in Bent 1929

The Black Oystercatcher (Haematopus bachmani) is a conspicuous member of rocky intertidal communities along the west coast of North America. Scattered unevenly from the Aleutian Islands to Baja California, with the vast majority (about 80%) in Alaska and British Columbia, Black Oystercatchers are, however, relatively rare; their global population probably number between 10,000 and 15,000 individuals. Completely dependent on marine shorelines for its food and nesting, the Black Oystercatcher is a monogamous, long-lived bird. Breeding pairs establish well-defined, composite feeding and nesting territories and generally occupy the same territory year after year, often along low-sloping gravel or rocky shorelines where intertidal prey are abundant. Pairs nest just above the high-tide line and use the intertidal zone to feed themselves and provision their chicks. Diets of adults and chicks consist mainly of molluscs; principally mussels and limpets. Parental feeding of offspring extends well after chicks develop independent flight.Pairs often abandon their territories in winter and form flocks; in areas of high mussel density, these flocks often number in the hundreds. Human- induced disturbances on islands where Black Oystercatchers nest have eliminated local populations.

The genus Haematopus is Greek for blood eye (red in Old World forms). Specific scientific name is by John J. Audubon for his friend, the Reverand John Bachman.

Brad studied Black Oystercatchers in Prince William Sound, Alaska, for his Ph.D. and remains interested in this fascinating shorebird.